How to teach grammar?

The Science: What the Research Says

Many people who have taught or learned a second language in a classroom setting have had the experience of attempting to memorize conjugation patterns, complex grammar rules, and their exceptions. But what is grammar? And how and when should it be taught in a language class to facilitate acquisition?

First, the term "grammar" is typically used when we mean to say syntax – the order and structure of words and phrases. For example, English has the syntax order Subject-Verb-Object, but many other languages (e.g., Japanese, Turkish) have Subject-Object-Verb order. "Grammar" also commonly refers to morphology rules in a language – the internal structure of words and the way they are formed. Some common morphological rules we teach in a second language (L2) classroom include pluralization, gender agreement, manipulating prefixes and suffixes, and the like. Usually, when people talk about "teaching grammar" they are not referring to pronunciation and vocabulary.

Grammar instruction has been the subject of much debate in both language teaching and second language research, mostly surrounding questions like Where do grammar errors come from? How much or how little grammar instruction is enough? Which instructional techniques work best? Is it best to structure a class around the most important grammar to learn? and even Should grammar be taught at all? Teachers might wonder whether learners must be explicitly taught grammar in order to acquire it or if they can simply absorb the grammar from instruction implicitly. Before diving into these questions, it is important to first understand how these terms are used to describe three concepts:

(1) the type of knowledge learners develop,

(2) the type of instruction the teacher provides, and

(3) the learning process as a whole.

Types of Grammar Knowledge

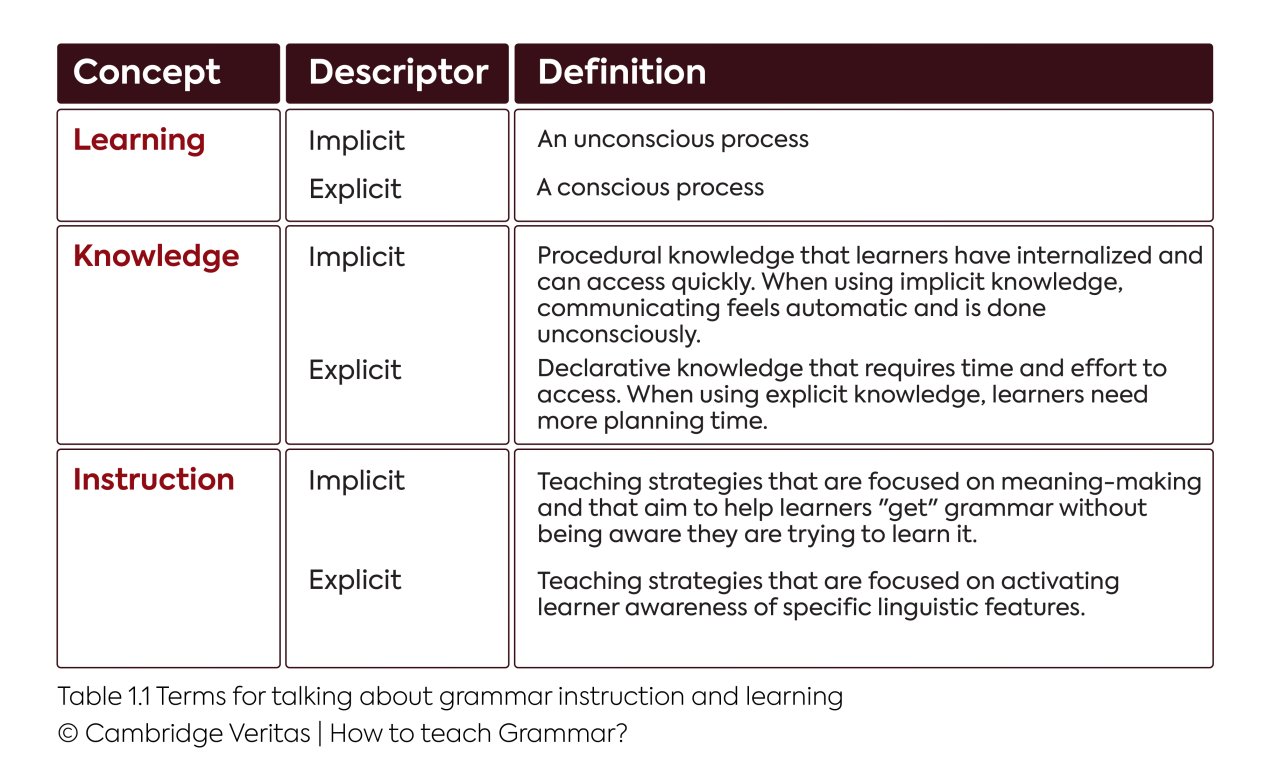

The terms implicit learning (unconscious, unintentional) and explicit learning (conscious, intentional) describe processes that learners experience in the classroom. For example, learners might acquire a new structure without intending to after hearing that structure used in a real-life situation. This would be an implicit learning process. On the other hand, a learner might explicitly study a conjugation table to learn how to conjugate a new structure. This is an example of an explicit learning process. The result of learning is knowledge, which can also be categorized as implicit or explicit. Implicit knowledge is procedural, automatic, quickly accessed, and internalized. If a teacher observes a learner spontaneously and fluently using targeted linguistic structures in natural conversation, that learner likely has some amount of implicit knowledge about that structure. Explicit knowledge is declarative, comprised of facts, controlled, and requires planning. If a learner can explain why and when to use a targeted linguistic form, that learner likely has some amount of explicit knowledge about that structure.

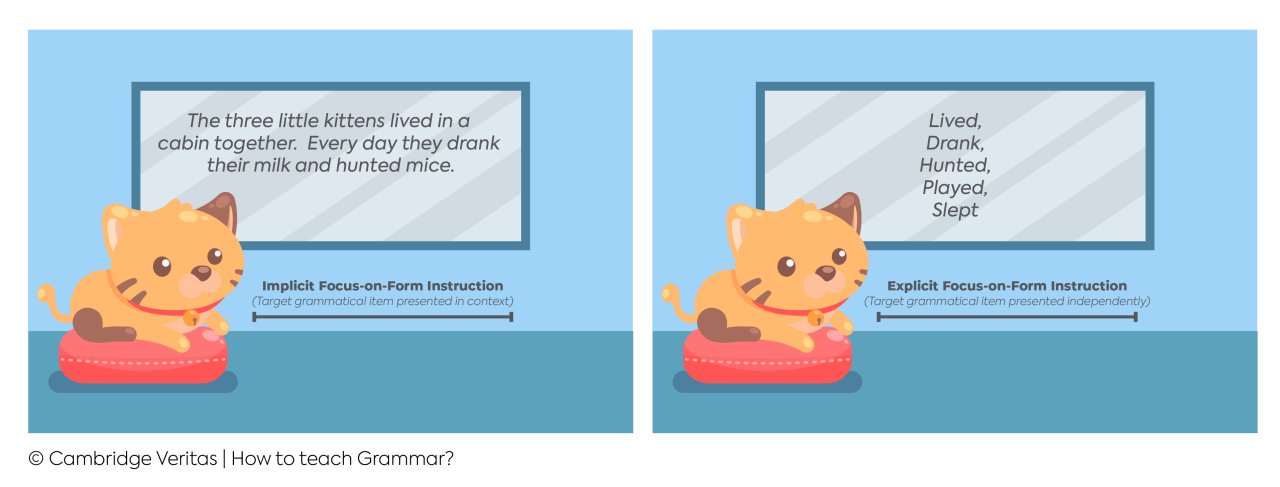

Just because a grammatical form is learned implicitly doesn't necessarily mean it will become implicit knowledge. Similarly, just because a grammatical form is learned explicitly doesn't necessarily guarantee that it will become explicit knowledge. Finally, implicit instruction and explicit instruction describe the types of strategies teachers use in class. These terms do not necessarily describe what kind of learning takes place or what type of knowledge is created. In this case, implicit and explicit just describe what sort of instructional practices a teacher is using. For example, in implicit grammatical instruction, teachers might provide learners with lots of comprehensible input (e.g., watching video clips) in the hopes that they will internalize the patterns that they hear (e.g., past tense verb forms) without conscious effort. In explicit grammatical instruction, teachers might provide learners with structured activities intended to draw learners' attention to a linguistic feature, guide learners in identifying a pattern, and provide them with opportunities to examine that pattern, like filling in missing verbs in sentences or playing a matching game involving verb ending (see Table 1.1 for a summary of these terms).

Just because a grammatical form is learned implicitly doesn't necessarily mean it will become implicit knowledge. Similarly, just because a grammatical form is learned explicitly doesn't necessarily guarantee that it will become explicit knowledge. Finally, implicit instruction and explicit instruction describe the types of strategies teachers use in class. These terms do not necessarily describe what kind of learning takes place or what type of knowledge is created. In this case, implicit and explicit just describe what sort of instructional practices a teacher is using. For example, in implicit grammatical instruction, teachers might provide learners with lots of comprehensible input (e.g., watching video clips) in the hopes that they will internalize the patterns that they hear (e.g., past tense verb forms) without conscious effort. In explicit grammatical instruction, teachers might provide learners with structured activities intended to draw learners' attention to a linguistic feature, guide learners in identifying a pattern, and provide them with opportunities to examine that pattern, like filling in missing verbs in sentences or playing a matching game involving verb ending (see Table 1.1 for a summary of these terms).

Relationship Between Instruction and Learning

Regardless of which type of instruction a teacher might use, it is important to reiterate that the kind of instruction does not necessarily describe the kind of learning that will take place. In other words, a teacher could be providing implicit instruction in class, yet some of her learners could still be developing explicit knowledge. Because of this, researchers cannot make any claims about what kind of instructional methods will generate what kinds of knowledge. Explicit instruction could lead to explicit or implicit learning. Similarly, implicit instruction can lead to explicit or implicit learning. This is because the learning processes activated during instances of instruction are controlled by the learner (even if they don't realize it!). For example, a teacher might be engaging in a "picture walk" (guiding the class through the illustrations of a book without reading) supported by some translated target vocabulary on the whiteboard. While the teacher might not be calling attention to the pronouns used to describe people in the picture, the learner might consciously think to herself, "The teacher is using 'él' when she talks about the boy in the picture and 'ella' when she talks about the girl. 'Él' must be for talking about boys and 'ella' must be for talking about girls." This internal monologue points to the learner having developed explicit knowledge about the Spanish pronouns él and ella despite her teacher using an implicit instructional approach.

Approaches to Teaching Grammar

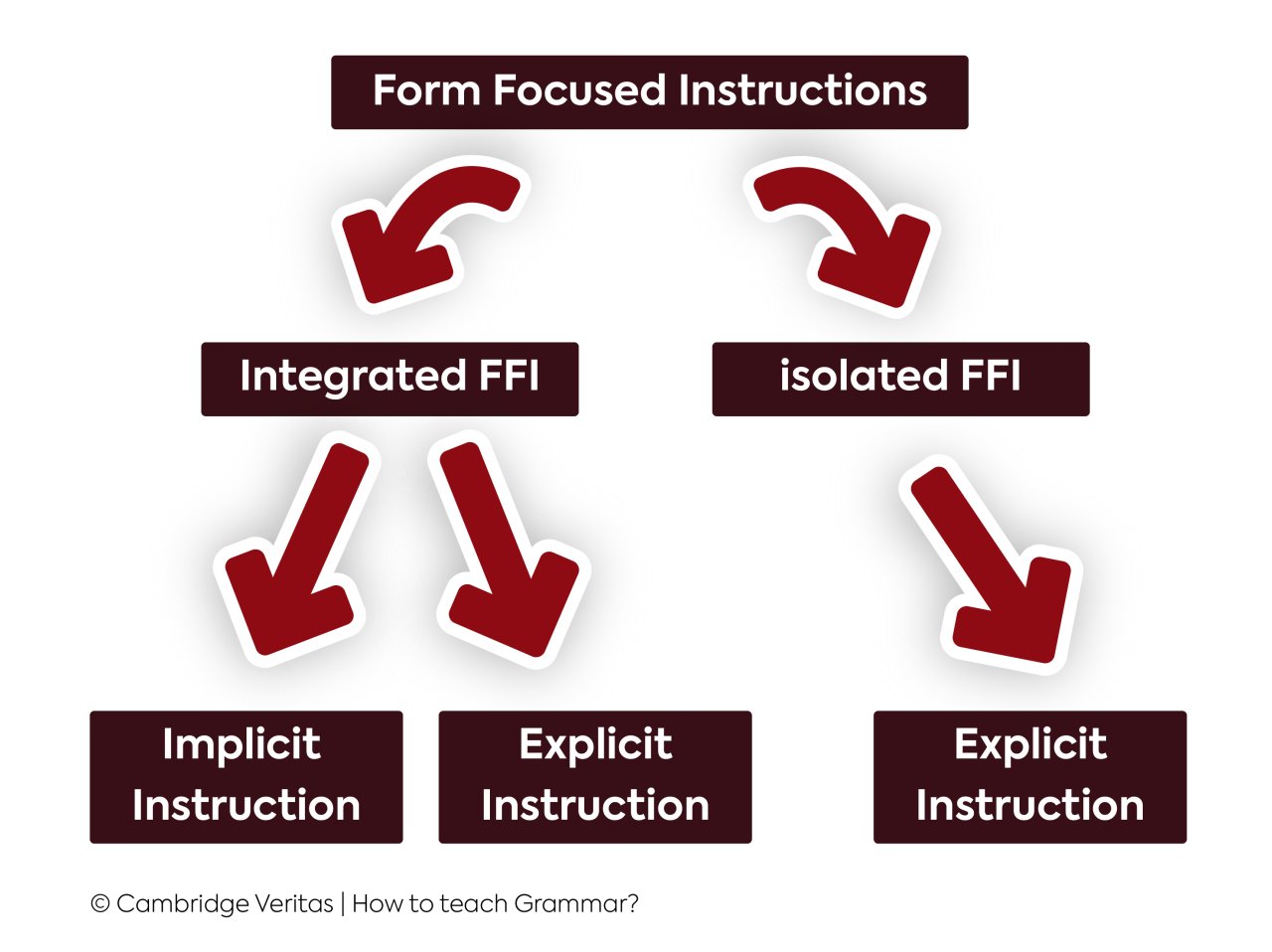

If, how, and when to teach grammar is one of the most studied and debated issues in second language acquisition (SLA) research and practice. If grammar should receive any type of instruction will depend on the theoretical/instructional approach taken by the program, curriculum, or teacher. If some attention is paid directly to teaching grammar at any point, researchers refer to this as form-focused instruction (see Figure 1.1). Some programs organize their entire curricula or syllabi around grammatical topics, where each unit highlights a particular grammatical form. In this approach, grammar is presented in an isolated context that is separate from a larger communicative task. Teachers typically use explicit instructional approaches in an effort to facilitate explicit learning processes that lead to the development of explicit knowledge. Teachers plan their lessons around the grammatical form, or forms, of the unit/week/day and students are expected to master them incrementally. This approach to teaching grammar is called isolated form-focused instruction, and research suggests that it builds explicit metalinguistic knowledge and awareness about the target language (TL). However, this approach assumes that language learning happens piece-by-piece, one grammar component at a time, in a linear manner. Researchers have found that language learning is actually much more dynamic and cyclical. Sometimes learners might seem to master a part of grammar but then suddenly start to make errors again. Other research has shown that learners pass through some universal stages of development and no amount of isolated form-focused instruction will help them acquire a form they aren't developmentally ready to acquire. We will return to this point momentarily.

Figure: 1.1

In programs that organize their curricula around communicative tasks, grammatical forms are more likely to be presented in an integrated manner as they relate to real-life skills that learners are developing in the TL. Though teachers might still use explicit instructional approaches to draw learners' attention to key linguistic features, the goal of their instruction is not for learners to develop explicit knowledge of how to form the future tense, for example. Rather, the teacher is using explicit strategies to help learners make form-meaning connections so that they may successfully accomplish the targeted task. This type of approach is called integrated form-focused instruction. Through this approach, learners are encouraged to think critically, deducing linguistic patterns as they learn to express themselves in more complex ways as they tackle increasingly difficult tasks. Forms are highlighted, through either explicit or implicit teaching strategies, exactly at the moment they are most needed for communication.

Aside from learner- and program-specific factors, the type of grammar feature itself has also been shown to impact how quickly or easily learning occurs. Internal properties of certain grammar features influence the kind of support or intervention learners may need. Certain grammar features seem to pass through universal stages of development. This means that grammar instruction, no matter how it is delivered, may not be able to alter the developmental order of acquisition. This has been found to be the case regardless of the first language(s) of the learners. For example, in English, third person -s has been shown to be a late-acquired grammatical feature by all English language learners, meaning if a learner is not developmentally ready, they will not acquire third person -s. Table 1.2 describes the well-studied developmental sequence for English language learners.

| Feature | Example | Order |

|---|---|---|

| "-ing" ending | I like swimming and dancing. | |

| plural -s | We see flowers, rabbits, and butterflies. | Earliest acquired |

| "be" copula | They are excited. | |

| "be" auxiliary | They are celebrating a birthday. | |

| a/the | I want a dessert. I want the cookie. | |

| irregular past | You went to the post office. | |

| regular past tense | He walked to the store. | ↓ |

| 3rd person -s | She travels every summer. | |

| Possessive -'s | That is the dog's bone. | Last acquired |

Table 1.2

The list in Table 1.2 contains just a few common grammatical features for a single language, English, and can't be used as a model for all features in all languages. However, these orders have also been found for other non-Indo-European grammatical features, such as question formation and negation. What causes learners from a variety of language backgrounds to acquire these features in this order? Much of the order of developmental sequences can be attributed to the frequency in which a feature appears, as well as how irregular its formation is. More common, regular features may be faster and easier for learners to master and do not necessarily rely on explicit knowledge to be mastered, especially if they are similar to features in the learner's L1. By contrast, unfamiliar and more irregular linguistic features may cause more trouble, requiring explicit instruction and practice opportunities. To master new grammatical features, research shows that learners need to first pay attention to these forms when they come across them in the input (e.g., in written text, spoken conversation).

In most instances, learners may pay attention to and often exclusively to the meaning of what they just heard because it takes so much effort to attend to meaning, especially for low-proficiency learners. If learners can "juggle" paying attention to both meaning and form of linguistic input, they may be able to pick up grammatical forms without explicit instruction or effort. If they cannot, it is not likely they will pick up grammatical form and instead will require explicit instruction. Grammatical features that learners cannot easily distinguish using a "bottom-up" observational approach (i.e., more implicit instruction) may necessitate a "top-down" processing approach (i.e., more explicit instruction) so that learners can better perceive the qualities of more challenging features.

Research into types of grammar instruction has mostly investigated different instructional strategies to compare how a group of learners who receive one type of instruction perform in comparison to a group of learners who receive another type of instruction. From these studies, findings suggest that instructional techniques that direct learners' attention to certain grammar structures, patterns, or features that are important for completing a task are more beneficial in comparison to using purely meaning-based instructional skills that are devoid of meaning attached to the forms. In other words, a sort of "middle ground" between entirely implicit instruction and entirely explicit instruction has been shown to be the most effective.

Oral or written corrective feedback targeting grammatical errors has also been the focus of many studies. As we discussed in that chapter, when learners' attention is drawn to grammatical errors through feedback, they are more likely to notice gaps between their own production and target-like production. So, the question is not figuring out if learners will benefit from making form-meaning connections. Instead, the question is to what extent and how frequently to draw learners' attention to form-meaning connections based on factors including their age, proficiency level, and the goals of the language program.

Role of Age in Grammar Instruction

Not all learners will approach grammar instruction in the same way. Younger learners have been shown to benefit more from implicit and meaning-based instructional techniques because they have more difficulty defining and describing language patterns explicitly. However, adolescent and adult language learners are less likely to make these kinds of important form-meaning connections on their own. For these adolescent and older learners, if they aren't noticing linguistic features, they are not going to be able to acquire them, even when provided with lots of exposure to those features. For example, explicitly pointing out grammatical errors has been shown to be effective for lower-proficiency learners and older learners, as well as for complex errors. In comparison, implicit corrective feedback, such as recasts, has been shown to be more effective for younger learners, higher-proficiency learners, and less complex grammatical errors. In order to incorporate new linguistic features into their communicative ability, some sort of form-focused instruction will be necessary. However, just because some learners need explicit instruction to master grammatical features does not mean they must be in the form of grammar drills. Grammar drills usually present grammar concepts in multiple, repetitive ways outside of a meaningful context or task. Drills are an explicit instructional approach that use explicit learning processes with the expectation that learners will develop explicit knowledge. While some learners who are able will transfer this explicit knowledge/practice to communicative situations, other learners do not. Grammar drills and explicit instruction usually focus on developing learners' accuracy in the use of grammar forms. The ability to accurately reproduce grammar forms during drills may or may not transfer to more communicative contexts.

The Science! Points to Remember

-

- The terms implicit and explicit can be used to categorize the learning process, knowledge, and instructional strategy.

- The type of instructional strategy (implicit and explicit instruction) does not necessarily describe the kind of learning that takes place. For example, explicit instruction doesn't always lead to explicit learning and implicit instruction doesn't always lead to implicit learning.

- In order to acquire new grammar features, learners must first notice it in the input and pay attention to meaning and form.

.png)